Over the past couple of months, I’ve held off on publishing anything in-depth about the COVID-19 situation. I didn’t think I had much to add to the conversation… until now.

My commentary during the early days of the virus outbreak downplayed the likely effects. I was clearly wrong with this view… but don’t regret the comments at the time.

Much of my approach is making bets based on the evidence at hand and from similar situations in the past.

At the time, that evidence pointed to a good chance that the situation would be contained (although still terrible). However, I quickly recognized the fact that we were dealing with something much larger… and at that point, I focused on how to handle it in the markets.

The reality was that the situation was developing so quickly, and we had such limited information, that I didn’t see any point in sharing or even forming opinions. It’s about as useful as speculating on where your toddler is going to go to college. You simply have no idea.

However, over the past couple of months, we’ve all learned a lot more… and we’re now set up to make a science-based decision about public policy.

That decision has massive implications for the investment environment and for our lives.

Of course, you’re probably thinking, “What does Enrique Abeyta possibly know about epidemiology?”

The truth is, I had never even typed the word before a couple of months ago.

That’s not relevant, though. Epidemiology is only one part of the equation about what should be done in the current situation. The bigger part of the question is really one about probability and public policy.

Epidemiology can provide some potential outcomes and probabilities, but not precise answers. That leaves us with taking those probabilities and outcomes and determining the best path going forward.

Now that we have more evidence, though, we have an opportunity to form a more informed opinion.

One of the keys to my investing approach through the years has been a “hit the ball where it is pitched” strategy.

This means while core strategies can work across almost any market environment, specific strategies can work better depending on that particular environment.

Understanding the backdrop of the economy and the stock market is key to figuring out how to both trade and invest. And right now, that backdrop is completely defined by the COVID-19 situation.

As a result, it’s important to share my thoughts on this outlook. While I’ve been relatively silent on these views, I’ve certainly spent a lot of time thinking about the situation. This has informed much of our trading during this period here at Empire Elite Trader.

So today, I’ll lay out those thoughts…

We Are Winning the War Against COVID-19

I’ll start with something controversial… but that I wholeheartedly believe to be true: The U.S. and the entire world have done a great job handling this situation so far.

The magnitude and velocity of this whole situation has been unlike anything we’ve seen in our (or any other) lifetimes. The fact that we sit here two months into this horrible situation and we only have roughly 320,000 deaths across the globe is amazing.

Each year, about 60 million people die worldwide, or 165,000 per day.

COVID-19 is insidious… and for the world to have stemmed the losses (so far) at these levels in this short a period of time and with so little information is terrific.

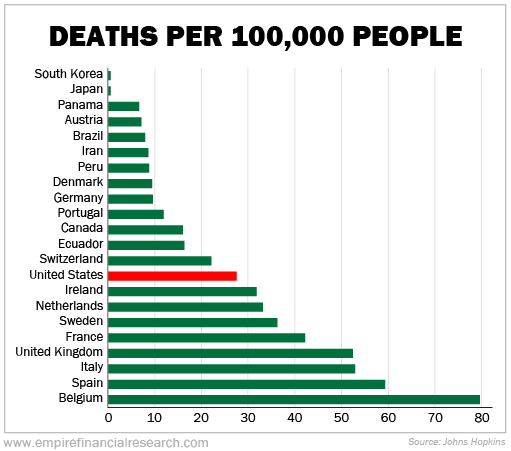

Here in the U.S., it’s popular to criticize the efforts to fight the virus – on both sides of the political spectrum – but we actually have performed in line with the rest of the highly developed world on a per capita basis. Take a look…

This statement is based on looking at countries where we have good data. Many smaller or less developed countries are showing even lower death rates.

Looking at the developed world in Europe and Asia, though, the U.S. is in worse shape than much of Asia and in better shape than much of Europe.

I’m not saying that there aren’t things that could have been done better so far in particular areas. In the U.S., the numbers out of New York City could have undoubtedly been much better and that whole situation has been poorly handled without a doubt. As I’ll discuss later, though, these “mistakes” may be different than people acknowledge.

But on an absolute and relative basis, these are good numbers overall. Given the context of the entire situation, governments across the globe have done a great job.

Let’s start with some things we now think the world “knows,” or what are high-probability bets.

1. There is no magic cure

Right now, a cure does not exist. Period.

We can look to historical precedent where a virus may recede for a period of time and maybe even mostly disappear… but this is a low-probability bet.

Everyone is in agreement that a cure doesn’t currently exist, and there’s unlikely to be one without a substantial amount of effort. It’s almost an impossibility that the virus will just magically go away in the next few months.

2. Don’t believe the vaccination and antibody ‘fake news’

The overwhelming consensus among scientists is that there are only two ways get past the virus – either a vaccine or herd immunity (the technical term is the herd immunity threshold, or “HIT”).

No other ways exist to get past the virus. As I mentioned, we’ve seen rare instances where a virus gets snuffed out, but those are extremely rare and low-probability.

As the crisis escalated, controversial headlines have appeared about antibodies… and the media has done a great disservice to the public in handling this concept.

There’s an old saying in the newspaper business: “If it bleeds, it leads.” Bad and scary news generates a lot of clicks. (The funny thing is, media companies don’t even make much money off clicks anymore, but they still feed on them like addicts.)

A common headline I’ve seen about antibodies that has driven many clicks is: “There is no scientific proof that antibodies provide immunity.”

The problem with this is that the media outlets forget the next sentence that should follow afterwards: “Nor is there scientific proof that antibodies do not provide immunity… but they have for every single other coronavirus and flu we’ve ever encountered.”

The scientific community leans overwhelmingly to the idea that antibodies confer some level of immunity for some period of time.

The catchy headline is technically true, because we haven’t had enough time to prove that antibodies provide immunity to the fullest extent of the highest levels of scientific testing and rigor… but the assumption that they do is a high-probability bet.

Antibodies not conferring immunity is a possibility, but not a probability.

Of course, we don’t know at what level of the population (50%… 60%… 80%?) they would provide immunity, but 75% is a likely number that many scientists have used.

What’s interesting about these headlines about antibodies is that the same people that claim they may not work do seem to think that a vaccine will work and confer immunity.

Vaccines use certain molecules from a pathogen (the virus) to trigger an immune response so that the body can then produce… antibodies.

If we don’t think antibodies work, then neither does a vaccine. And in that case, we have much bigger problems.

For now, though, I’m confident in sticking with the overwhelming scientific consensus that a vaccine or eventual herd immunity is the only way out of the current situation.

3. We have different time frames for a cure or vaccine

While herd immunity should work, it’s a painful and horrible way to get to the solution, and many people will die.

The much better outcome would be a cure or a vaccine. This is our best outcome. But the critical question arises of how long it will take to develop one. Most of the analysis is focused on three possible outcomes: six months or less, 12 to 18 months, or more than 18 months.

The vast majority of vaccines (if doable) take many years. However, given the focus of the entire world on this ordeal, the consensus is that a shorter time frame is the likely outcome.

We don’t have an “official” poll of scientists, but based on our team’s extensive reading of the consensus, the odds of each of these seem to come down to a 10% to 15% chance in six months or less, 75% in 12 to 18 months, and 10% to 15% in more than 18 months.

Remember, these odds are for my discussion of the options in front of us globally.

‘Plan the Trade and Trade the Plan’

This phrase is something I say in regards to trading, but it could refer to any process for making a decision while dealing with uncertainty.

When global governments took unprecedented action several months ago to shut down the world’s economy, this was done based on a simple group of assumptions. Let’s review those now…

- Shutting down the economy will slow down the transmission of the virus.

- With proper treatment (i.e., a hospital bed, intensive care unit, ventilator, etc.), the chances of survival increase.

- We don’t have much information about transmission, treatment, etc.

These were the assumptions behind the “flatten the curve” idea.

In this case, the “curve” is the number of new cases that would occur. It was a simple goal. If the curve flattened, it meant we would more likely have enough hospital beds to treat people and more time to figure out how to deal with the whole situation.

With this in mind, we can now consider the options that we’ve been dealing with and what lies in front of us.

With the entire world still in a theoretical “80%” lockdown, we had about 4,500 deaths yesterday across the globe.

This is a trailing indicator, as it’s reflective of where we were roughly a month ago – which was with the world closer to “90%-plus” locked down.

We actually have data from Google showing mobility… and the U.S. – across multiple measures – is down about 37% from pre-lockdown.

As I said earlier, this is a great outcome across a global population of more than 7.7 billion.

But the question we don’t have an answer to is what this number of deaths looks like if we were in a theoretical 25%, or 50%, or 75% lockdown.

Unfortunately, the only way to figure that out is to attempt it. So let’s look at the probabilities of the timing of a cure from above…

1. Six months or less (10%-15% probability)

In this case, the high-lockdown option could be supported – although the economic cost may still be too high.

Let’s say we go this route, and even have a slightly higher level of mortality at 5,000 per day. That’s another 900,000 deaths, bringing the total to roughly 1.5 million.

It’s a horrible figure… but less than 0.02% of the global population. Given the worst-case estimates without a lockdown, this would be a great victory.

The economic damage is terrible, but the period is only six months. And with monetary and fiscal support, the global economy will recover – perhaps not immediately, but most likely across the next few years.

One thing to think about: Using the U.S. as the proxy, about 1.3% of our country’s population was infected per month during this most recent period, and we’re at roughly 4% across the country right now. At the end of these six months, we would be at just about 12% antibodies.

Remember, this scenario is only a 15% probability at best.

2. 12 to 18 months (75% probability)

This is the high-probability bet.

If we stayed on extreme lockdown, global deaths would be two to three times higher than our first scenario, coming in at roughly 3 million to 5 million (or 0.06% of the population).

This is still only a small portion of the population, but the economic damage would be devastating.

There’s no real way to accurately model the quantitative effect of this collapse of the global economy on human suffering and mortality, but it’s big – perhaps 10 times the number of direct deaths from the virus.

At the end of this period, we would have been hovering at about 25% to 30% antibodies with an economy in shambles. But what if the next scenario is correct?

3. 18 months or longer (10%-15% probability)

Game over. I don’t think I need to spend too much time explaining this, because we all know that it’s bad.

Ultimately, we’re left with one low-probability outcome where a continued strict lockdown might make sense from a public policy perspective. This looks like a pretty bad bet.

There’s another option, though. And it’s the one the U.S. is actually following (albeit in a rather disorganized fashion)…

The Swedish Model

Sweden has received a lot of press for taking a differentiated approach. But it’s one that I would still call a middle ground.

It essentially revolves around expecting their people to use common sense and respect some of the core principles of a lockdown, but it otherwise keeps the majority of the economy open. Gyms, schools, restaurants, and shops all remained open throughout the spread of the pandemic.

Using our theoretical 0% to 100% scale for economic lockdown, it looks like Sweden would be at 40% or so – maybe even less. This is where much of the U.S. is getting to right now.

I mentioned the 37% decline in the U.S. from the Google mobility data earlier. Sweden was “locked down” to about a 21% decline on the same measure.

I’ve seen a lot of commentary about how something like this wouldn’t work in the U.S. because of our different cultures, economics, and geographies. I disagree.

For every advantage Sweden has locally that we don’t, we have one that Sweden doesn’t have. Ultimately, these are complex human economic systems and it’s unlikely that any major country or economy has any real material advantage over any other. This is another controversial view… but unless someone has a cure, we’re all in the same boat.

The better point about Sweden is that even with a lower degree of a lockdown, the country never tipped over into overwhelming its hospital capacity like the worst-hit countries – Spain, Italy, and Belgium.

The most recent data from Sweden imply that its hardest-hit area – Stockholm County, around the capital city – shows an infected rate of about 25%.

This means the region had a growth rate of about 7.5% of the population per month. Note that the county’s mortality rate has been about 0.32% based on these numbers.

And Sweden’s net hospital admissions have been falling for about a month. This implies that herd immunity may have been achieved at a much lower level than expectations.

Some emerging theories are out there saying that some people may have different levels of biological susceptibility. Simply put, some people might be much more likely to contract the virus than others.

This means that in the early stages, the infection rate looks high – as those highly susceptible people get the virus – but then it slows down as this population is exhausted.

This isn’t as a result of social distancing, but rather the biological factor… and it could mean herd immunity rates are much lower.

I’m not saying this is what will happen, but it’s a distinct and positive possibility.

Sweden’s mortality rate is worse than the other Scandinavian countries that were more locked down, but its economy, while still down, has done much better.

Also, because Sweden never tipped over into overwhelming its hospital capacity as it flattened the curve, its mortality rates are better than other major European countries like the U.K., Italy, and Spain.

Remember, the country is at 25% antibody prevalence in its key metropolitan area.

If we’re aiming for 75% of the population to achieve HIT, then Sweden is currently about a third of the way there.

If this is achieved at much lower levels – which Sweden’s declining hospitalization rates might imply – then the country could be much further along.

A theory exists that says different populations have big differences in susceptibility to infection. If this is the case, the most susceptible have already been infected in “hot spots” like Stockholm County and New York City. This means “herd immunity” could be as low as 25%.

And based on history, another argument states that warmer weather can significantly hamper these viruses. Consider the lower infection and mortality rates in Florida right now as an example… The state hasn’t exactly been a paragon of lockdown activity.

This reminds me of the headline about antibodies not working. We don’t have conclusive proof that either of these theories will play out, but they have in the past… and current evidence is emerging.

If either of these turn out to be true, then this is great news.

But what about the other countries that the media has hailed as big success stories?

Losing for ‘Winning’

This comes back to a popular concept that has troubled me since the beginning of this crisis.

Observers have been looking at countries that have quickly stemmed the spread of the virus, like South Korea, and pointed to these as “victories” or signs of their superior policy.

One of my first arguments was that nothing is so different to life in South Korea that makes the population immune or eventually completely eliminates the spread of the virus.

There may be some factors – like existence of previous viruses in Asia – that means they could be less susceptible but this is not a difference of 3% versus 75%.

Again, no magic cure exists… and it’s highly unlikely the virus will just disappear.

Sure, South Korea might be able to close itself off and control the spread, but it won’t be able to eliminate the virus.

Even if the country brings down cases to a minimal amount in the context of a closed society, it eventually has to open up again to the rest of the world.

Unless a cure (vaccine) appears, the country will become vulnerable again.

Or, South Korea could stay closed until a cure is developed. This is making a specific bet, and it gets to my point…

I’m not saying the country made a mistake, but doing what it has done may just be delaying the same eventual outcome as everyone else: that South Korea also needs to achieve herd immunity.

With this outcome in mind, let’s turn our attention back to our country…

Where We Stand in the U.S.

Based on just about 1.5 million confirmed cases across more than 320 million people, the U.S. is at about 0.45% confirmed cases as a percentage of the population.

We’ve heard ad nauseum about the lack of testing, and the strong consensus is that the actual numbers are much higher.

Today, it appears that key hot spots like New York City are at about 20% of the population, while the vast majority of the country is in the 2% to 5% range.

For our simple analysis, let’s say the number is 4%. (Note that at 20%, New York City single-handedly pushes the national number up 0.4%.)

If we chose 75% as our number, this means that New York City is possibly a third of the way there… while the rest of the country is way behind.

These numbers match up with European data, where hot spots have been in the 10% to 30% range and other areas are in the 2% to 10% range.

By that measure, New York City might actually be in the best position of any location in the U.S. going forward.

This isn’t to say that the situation couldn’t have been handled better there… but if a vaccine takes longer to develop, then New York City has the opportunity to return to normalcy sooner than more “successful” urban areas like San Francisco. In fact, it’s likely that New York City will eventually open in a much more “successful” fashion than San Francisco.

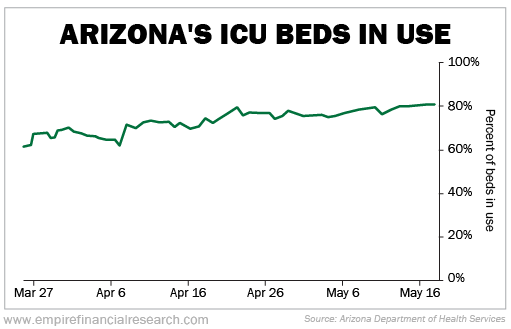

We need to consider what mortality looks like when flattening the curve. Let’s look at my home state of Arizona, which is a good example of what much of the U.S. looks like…

Right now, estimates are for about 3% antibody prevalence here – similar to the country as a whole. We never hit hospital capacity. Take a look at the chart for where I live in Maricopa County…

In fact, we have remained at about 80% of capacity, which is only a small increase from previous levels. This is key to maintain going forward.

And looking at the Google mobility data again, Maricopa County has been somewhere between the U.S. overall and Sweden in terms of the lockdown.

Our COVID-19 mortality rate has been close to Sweden’s at 0.28%.

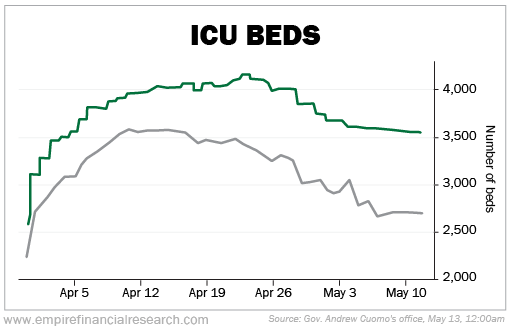

Here’s a similar recent chart of ICU beds for New York state…

It doesn’t capture the fact that New York City went right up to the edge and without a doubt saw some deaths that otherwise could have been prevented with a slower spread of the virus.

Based on a New York City antibody prevalence rate of 20%, the fatality rate is roughly triple that of Arizona or Sweden, or 0.93%. Best estimates of the hardest-hit parts of Italy and Spain also come out a little worse than this, or roughly 1%.

And consider this: If you’re young, you’re more likely to die in a car crash than from COVID-19.

The difference in fatality rates from the virus has been discussed a lot, but it’s powerful to see the numbers. Take a look at the data on deaths by age group as a percentage of the people that have had COVID-19 in Arizona…

This means that in Arizona, where hospital capacity is average, if you contract the virus and are under the age of 55, you have a 0.0017% to 0.055% chance of dying.

Remember, we achieve herd immunity at some percentage below 100%. This means the average person in that age group has between a 25% to 75% chance to contract the virus. This further reduces those percentages.

And the numbers don’t look as bad when you consider auto accidents in the U.S. Let’s look at some statistics…

- More than 320 people in U.S.

- 6 million auto accidents

- 2.67 people involved per vehicle

- 16 million people involved

- 38,000 fatalities per year

- 0.012% fatality rate

In other words, you have a 5% chance of being in a car accident in any given year. If you’re in one, you have a 0.24% chance of dying. Overall, roughly 12 people per 100,000 die each year from a car accident.

And consider the distribution amongst age groups for auto fatalities…

If you’re 16 to 25, you’re as much as two times more likely to be in a fatal accident than the rest of the population. This is 0.015% to 0.02% probability. For the youngest age group, this is 10 times greater than dying from a COVID-19 infection.

Additionally, the oldest age group is also more likely to die – just like COVID-19. It’s more evidence that shows the elderly are our most vulnerable population group across the board.

We constantly make day-to-day trade-offs where we accept a risk of fatality in order to live our lives.

Of course, an individual can make decisions while driving that increase their chances of dying – for instance, driving while impaired or driving aggressively.

Similarly, people can make decisions in a semi-locked-down economy (such as washing your hands and practicing social distancing) that could also decrease their probabilities of contracting the virus.

For two-thirds of the U.S., the mortality rates are more than acceptable in a semi-locked-down economy.

However… hospital capacity is everything.

This comes back to the whole idea about flattening the curve. There was never a scenario where we simply eliminate the virus, nor one where it magically disappears.

Instead, the idea is that with proper hospital care and enough capacity, we can manage to do our best. And based on the existing evidence, it seems like a managed mortality rate might be around 0.5%.

Remember, Sweden’s Stockholm County works out to a 0.32% rate.

New York City looks like it could be as high as 1% but it could also be as low as 0.5%. This is a situation where we pushed or exceeded the “management” of hospital capacity… but New York City is likely also now at 20% antibodies.

Many people are ignoring the critical issue that flattening the curve means preserving this hospital capacity but allowing people to actually contract the virus in as controlled a fashion as possible.

If we can “manage” the hospital capacity, then the only logical “bet” here is to let the virus run its course to allow herd immunity while not exceeding the level that overruns the medical system.

(Remember that these mortality rates should be improving as we continue to refine our treatments. Until a vaccine is developed, there’s likely a limit to how much these rates can get better… but they can improve substantially).

This way, we have “hedged” our bet in case the development of a vaccine takes longer. All of this comes back to the following million-dollar question…

What Should We Do From Here?

With so much “information” out there and so many cross currents, it’s useful to frame the choice in front of us in the simplest terms. We have two choices…

A. Stay mostly closed as an economy

This is the bet that vaccine development will happen quickly. If this happens, we still lose more than a million people globally and 150,000 in the U.S. to the disease. The economy is deeply wounded but likely survives. This is a low-probability bet.

If a vaccine takes longer to develop, we still lose millions of people (perhaps 500,000 in the U.S.) and our economies take decades to recover.

B. Open up like Sweden (and much of the U.S. today)

In this scenario, likely deaths in the short term go up… but we make further progress every day to herd immunity.

If herd immunity is accomplished at much lower rates, we may reach this point well before a vaccine is available. If we stay shut down, we won’t know for a long time whether herd immunity is achieved… and the damage to the economy is massive.

In this scenario, though, it’s likely that many people will get the virus… It’s important to acknowledge this.

For the vast majority of people, it won’t be fatal. That doesn’t make it good in any way for those that contract the disease, but it’s the reality.

There’s also an option for individuals – if you do not want to participate in the reopened economy out of concern for the virus… don’t. This is what one would be doing in the “stay closed” scenario anyway, and anyone is free to do it.

So with those as our choices and based on the evidence that we didn’t have before but now do, here’s a relatively straightforward idea with three components…

1. Open the economy to ‘Sweden levels’

I don’t have a great quantitative measure of what this means… but qualitatively, it looks to be what much of the U.S. is currently doing: diminishing capacity for public spaces, enacting social distancing guidelines, wearing masks, shutting down the largest communal events, and expecting your citizens to follow the rules.

I absolutely do not believe that this is somehow impossible for Americans to do. The net outcome across the broad population will be that enough social distancing can continue to flatten the curve.

States, counties, municipalities, and other jurisdictions can also adjust these rules according to changes in hospital capacity.

Remember, the key figure to watch isn’t the number of cases… but rather hospital utilization. If the numbers get much beyond 70% to 80% of capacity, then they should tighten the rules.

Some people would argue that going back and forth between loosening and tightening would be more detrimental, but I disagree, mostly because it gives us the option that something better happens. If we stay fully locked down, few of the things that could go right for us can happen.

And remember, businesses don’t have a mandate that forces them to open against their will. If a business doesn’t want to be involved, it doesn’t have to be.

2. Expand hospital capacity

I’m shocked that this hasn’t been a greater topic of conversation.

Our best bet is to keep hospital capacity at a manageable level, or optimized for the best possible mortality outcomes. If we can hold those levels, we can allow the virus to continue through the population until we achieve herd immunity.

So why don’t we take the trillions of dollars being spent on stimulus and spend it on expanding hospital capacity?

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. military has 5,500 fixed-wing aircraft, and the cost to replace that fleet over the next 30 years is $630 billion. This works out to $115 million per aircraft. The maintenance of that fleet costs $4 billion per year.

This $750 billion investment is kept in case of an emergency (i.e., a war) where we need to risk some lives to save millions.

Now, consider that it costs an average of about $1 million to build hospital bed capacity.

Looking at at hospital capacity in the top 300 metro areas in the U.S., we need to calculate how many beds we would need at different levels of herd immunity.

This range is an additional 200,000 beds at 20% herd immunity, 900,000 beds at 40%, and 1.6 million beds at 60%.

Building 1 million hospital beds would cost us $1 trillion. So why don’t we do that?

These can be flexible in terms of location, operability, and staffing – the same way we have the armed forces and a national guard. And with economies of scale, the eventual cost per unit would fall dramatically.

This is the best kind of high-quality infrastructure that could be built using American-made products – which puts people to work.

It will all take some time… but why don’t we start right now?

The worst-case scenario is that the vaccine arrives quickly and we don’t need all the added capacity… but we’ll be better prepared for the future.

This is the single most important thing we could be doing right now.

3. Quarantine the endangered

This will be unpleasant… but we should take the portion of the population that is most at risk (25%) and put them in the same lockdown that we’ve all been in over these past few months.

This is mostly the elderly and the immunocompromised, and I would combine this with massive infrastructure spending to help them through this period…

Spend money to help the sick and elderly.

Of course, the details are more complex… but considering the critical period, this investment is helping everyone.

It’s what we have seen happen in Sweden, where the country dramatically increased spending to help its oldest citizens.

The Best of the Bad Outcomes

While I’ve touched on a number of controversial ideas in this conversation about the virus crisis, I bet my first statement is still the most controversial of all: The U.S. and the entire world have done a great job handling this situation so far.

Objectively, in the big picture, the mortality rate has been managed much better than the stated worst-case scenarios. Global economies have been very “injured”… but look like they can still heal.

Governments across the globe made all of these huge moves with almost no data (we didn’t have a choice) and did it all in two months. That is all astounding and positive news.

In particular, in the U.S., our system is working the way it’s supposed to work.

Our federal system has come under some criticism in recent years, but our country has a balance between the national, federal government and state and local governments.

The great thing about this model is that we can try many things within the context of our economy and political system. Just like how individual European countries can employ different strategies economically (or against the virus), we can do the same with our individual states.

We do so along a common framework, but our country ultimately empowers states to find their own way. This system embraces the humility that in complex human systems, it’s impossible to truly know an outcome without experimentation.

This is what is happening right now across the U.S. Each state and locality – within a broad framework – is trying different methods to deal with this crisis.

But the outcry about the lack of federal “leadership” is misguided. I’m not defending the “tone” of most politicians – either local or federal – but the system is working the way it should.

The U.S. is at its best when it takes risks and lets its states, cities, and population make their own educated decisions.

It’s easy – and psychologically satisfying – to criticize… but the U.S. and the world are reacting incredibly well in the context of this incredibly difficult situation.

So for us here at Empire Elite Trader, the key now is what we do next from an investment standpoint…

What Does All This Mean for Investing?

Going back to where I started this conversation (and the reason I write this newsletter) – what does all this mean for the investing environment?

As I said earlier, the economic and stock market backdrop drive the opportunity set and the particular strategies that an investor should employ.

Here at Empire Elite Trader, we’re focused on shorter-term opportunities and taking advantage of volatility.

The goal here is to hold positions for less than six months and make quick gains of 10% to 20% or so by (hopefully) taking little risk. This is a tactical strategy.

Given the current market volatility, right now is a great time to be a tactical trader. Considering the increasing stabilization in the virus situation – but still with heightened volatility – I can’t think of a better time to be a trader.

With that said, we’re not adding a new position to our portfolio in this week’s issue… but stayed tuned. I’m keeping my eye out for the perfect opportunity and will let you know when the time is right here at Empire Elite Trader.

Regards,

Enrique Abeyta